“Purim as Queen Esther’s ‘Coming Out.’” We don’t tend to think of holidays as occasions into which we grow, but that is, in part, what they are. Thirty years ago, as a child growing up in the shah’s Iran, Purim was just another holiday to me. Later, on my family’s departure from Tehran — when I was just beginning to understand the meaning of introspection — the joy that Purim had once occasioned began to dissipate. The holiday went from joyous to tragic: the bitter reminder not of what our people had once done, but of where our people had once called home.

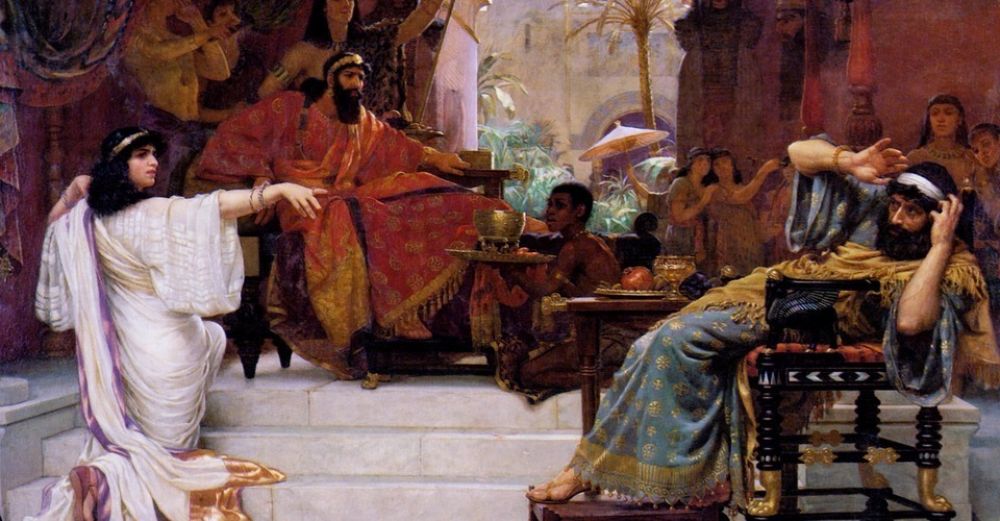

And this year, in the midst of all the controversy over my native land, Purim has taken on yet another meaning. Peel away the fanfare — the palace, the riches, the envy and the feuding — and what remains in the Book of Esther is a coming out story, the simple tale of a woman daring to reveal her true identity. In fourth-century BCE, in what is today Iran, a woman admitted to being a Jew. The truth shocked her unknowing husband. That he was the king enhances the drama, but is, otherwise, entirely irrelevant. It is the revelation and subsequent shock that are crucial. A woman’s most intimate companion did not know the truth about her, thereby casting a doubt over the genuineness of their intimacy. Though some 25 centuries have passed, the Iranian Jew’s quandary remains much like Esther’s.

The Forward, March 10, 2006